Zakariya Multani suhrawardi R.A ka seerat

Bahauddin Zakariya (R.A)

This is a hagiography, written in the old tradition of tazkira literature, of Shaykh Bahaud-dn Zakariya Multani (c. 1170 – 1267), who was the most prominent Sufi of the newly established Suhrawardi order in the regions of the then Northwestern India.

Given the nature of the book, I did not expect a comprehensive analysis of the belief system of this sufi, but, in addition to excessive praise, I at least expected to get a general view of his thought. In this respect this book has been an utter disappointment. So much so that I embarrassed myself by reading it from cover to cover.

The author sets out with the greatness and piety of the Shaykh, his steadfastness in faith, tireless quest for knowledge, travels to far off lands in search of the Truth (whatever it means), his numerous miracles and wonders which are identical to the miracles ascribed to the prophets, his ability to read the mind, knowledge of the unseen and much more.

This book, however, contains some factual information about the life of Shaykh Zakariya and recounts a few prominent achievements for which he is known.

He left Multan (his birthplace, now in Pakistan) in early youth and set out on a long and perilous journey of Muslim mainlands for higher education in Islamic disciplines. He is reported to have travelled from city to city for almost three decades: Tus, Neshapur, Bukhara, Samarqand, Damascus, Aleppo, Mecca, Madina and finally Baghdad, spending time with the prominent teachers, before he returned to Multan in the latter part of his life.

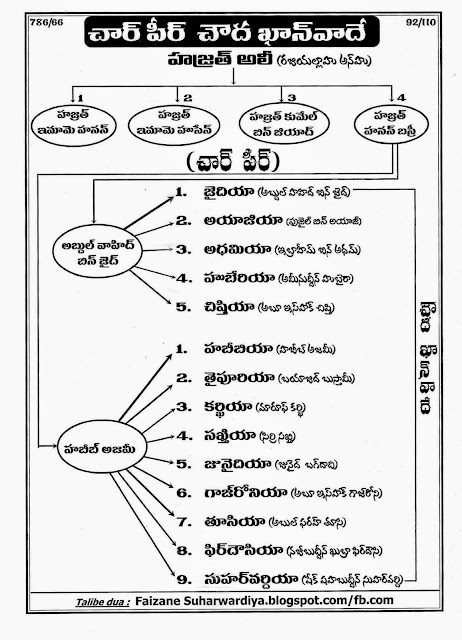

He was primarily a jurist who, during his stay in Baghdad, got attracted to the teachings of Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi (more about him later). The latter initiated him into the Suhrawardi tariqah and ordered Zakariya to return to his homeland to spread the message of Suhrawardiyah.

Shaykh Zakariya’s life and activities back in his native city gets some detailed attention in the book. He belonged to a family of religious judges (qadis), a very wealthy family which enjoyed influence with Muslim overlords. In time he became heir to the family fortune which, according to the book, he spent in the cause of religion. He constructed a huge madrassa in Multan which housed students, travellers, shelterless and teachers imported from Muslim mainlands. His fame and piety won a lot of converts to Islam, which, in turn, he sent over to far off lands for tabligh. Shaykh Zakariya is reported to have sent teams of students to Far East countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and other areas to spread Islam. These tablighis have reported to won multitudes of converts.

Other aspects of his life is schism between him and the governor of Multan Nasir al-Din Qabacha. The latter ruled the province under the authority of the Sultan of Mamluk Dynasty (Slave Dynasty of Delhi), Sultan Shams al-Din Iltutmish. The governor of Multan is reported to have been jealous of the Shaykh and tried to discredit his image among the people. He used many means to achieve his end but, according to the book, failed. So we don’t know the nature of the dispute between the Shaykh and the governor, whether it was theological or just political or a mix of both, because the author tends to ascribe all opposition to the Shaykh a result of jealousy and ill-will; a likely explanation a hagiography can offer.

We can attempt a method of association and try to look into the beliefs of his master, Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi, to get an idea of Shaykh Zakariay’s views.

According to sources other than the book under review, notably Sayed Hossain Nasr and Mahdi Aminrazavi, Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi (1154 – 1191) is known as the founder of the ishraqi (Illuminationist) school. He was a philosopher in his own right who challenged fundamental views of Ibn-e-Sina’s peripatetic philosophy (originally an import from the Greece/Aristotelian thought). Without concerning with his philosophical ideas and their application to Ishraqi sufism, suffice it to say that Suhrawardi’s sufi thought depended on his central theory of the Lights. He perceived reality as being divided into Light and Darkness. The immaterial Light of Lights (nur al-anwar) is God through which further flashes of light emanate. These flashes of light have lesser intensity to that of the Light of the Lights. The smaller lights then interact with each other, pass through the intermediary world (alam al-mithal) and give rise to new lights of various intensities. This is Suhrawardi’s cosmology in a nutshell which doesn’t really make sense without further elaboration but this is beyond the scope of the review.

He also believed that existence per se, of humans and other living beings, is an abstraction of mind and doesn’t constitute part of Reality. He denied, in opposition to Ibn-e-Sina, that there is a fundamental form to every material object which could be known through inhering. Interestingly, he had also rejected the theory of vision which was current in those days: Human eyes emit light which falls on the objects which makes the vision possible. He claimed that the light actually emanates from the objects, which links back to the Light of Lights (God) and that the eye, which is a part of darkness, is merely filled with that light.

Suhrawardi’s cosmology and Ishraqi (Illuminationist) ideas had big influence on Mullah Sadra who combined his ideas and that of Ibn-e-Sina’s peripatetic philosophy to create his own.

Suhrawardi was in Syria when he was declared a heretic. He was executed on the orders of no other than Sultan Salah al-Din Ayyubi himself.